Reckless Persistence In Hope

Reckless Persistence

By Fr. Jerry Pokorsky | Oct 28, 2024

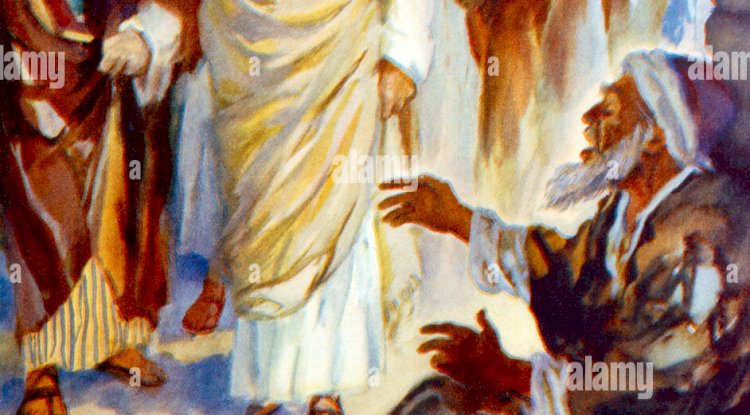

Bartimaeus, the blind beggar, had a persistent and reckless faith (cf. Mk. 10:46-52). When he heard that Jesus was passing by, he cried, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” Despite the rebukes of the crowds, he cried out all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” Jesus stopped and said, “Call him.”

Throwing off his mantle, he sprang up and came to Jesus. He said, “Master, let me receive my sight.” Jesus rewarded his persistence. He said, “Go your way; your faith has made you well.” And he received his sight and followed him on the way.

Like the Canaanite woman who relentlessly begged the Lord to cast out the demon afflicting her daughter (“Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table”), Bartimaeus is an Apostle of Persistent Faith.

The Divine Artist created us in His image. When we discover ourselves with God’s grace, we uncover God’s imprint. When we discover Jesus, we find our purpose and destiny. In humility, we begin to see ourselves as God sees us.

The Psalmist prays, “I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” (Ps. 139:14) St. Thomas, with his usual clarity, affirms that God created us as social beings in the unity of body and soul. Our body expresses our soul. Death is unnatural, and God will reunite our body and soul at the Last Judgment for eternity.

By God’s design, our eyes gaze outward. This configuration assists in avoiding self-absorption and narcissism. We even acquire insights that others are unable to see in themselves. A medical professional may neglect his health but remains a competent and reliable doctor. A priest may suffer the usual personal deficiencies as he remains an effective confessor. We need persistent introspection to become aware of our personality quirks and shortcomings.

So honest introspection is also necessary for humility. We are God’s handiwork. Our intellect and will are the highest faculties of our soul. We think and we choose. Our memory serves our intellect. Like a sizeable memory in a computer, a good memory facilitates our thinking. Memory games—such as memorizing the multiplication tables – help to exercise our memories.

A healthy imagination provides us with visions of our free-will choices. John Kennedy was a man of vision when he promised in 1961, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” We succeeded.

Our memories and imaginations are great gifts but easily abused. St. Ignatius teaches the Devil has access to the chambers of memory and imagination, but not – without our permission—the intellect and will. Memories easily remind us of past sins. Pornographic images may afflict our imaginations.

Our emotions encompass body and soul. We like and desire a hamburger. When we eat a hamburger, we experience joy. A soldier in battle despises the prospect of injury. When he is wounded, he is sorrowful. When the sorrow is intense, it becomes gnawing anger. Anger affects our thinking and causes changes in blood pressure.

However, even unpleasant emotions like anger needn’t be sinful. Mary was sinless in her sorrow at the foot of the Cross. St. Paul writes, “Be angry but do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger.” (Eph. 4:26) Every proportionate emotion ruled by right reason is natural and good.

Many reduce our humanity to a disproportionate bundle of emotions. Popular culture teaches us to “trust our feelings.” Baloney. Our emotions should not rule us. We should rule our passions. But, because of the effects of Original Sin and our sins, our passions are often unruly.

A soldier (or anyone else) suffering from PTSD may turn to alcohol and drugs in a vain attempt to extinguish burning anger from terrible experiences. Indeed, psychological disorders that lead to sexual dysfunction are often (but not always) rooted in childhood trauma.

In the name of Jesus, we need priests to forgive us of our sins. We may also need the help of morally upright therapists to help us sort out the bundle of our emotions. Sin has rendered our emotions untrustworthy. So we aim for clarity of thought and righteous choices.

Conscience – for believers and unbelievers – is the voice of God. Authentic Church teaching and the Ten Commandments purify, reinforce, and form a good conscience. We need persistent vigilance and virtuous habits to help us control our emotions.

The virtue of prudence evaluates our prospects. A prudent man habitually identifies possible options, dismisses evil choices (as conscience dictates), and chooses the best alternative. A Just man habitually directs his free will to fulfill our duties to God and man.

The virtues of self-control (temperance) and courage (fortitude)—as guided by prudence and justice—regulate our emotional bundle. In self-control, we consume only one hamburger instead of two. With courage, we take control of and direct our hopes, disappointments, fears, and anger. God’s grace – especially as we receive it in the Sacraments – permeates our minds, emotions, and bodies.

Our actions form us. Thoughtful Catholics strive with God’s grace to see the sins rooted in their hearts. Occasionally, our inner complexities need a tune-up, a minor repair, or an overhaul. Conversion not only changes our behavior. Conversion reveals who we are. “You will know them by their fruits.” (Mt. 7:20)

These body-and-soul complexities make up our humanity. But humble self-knowledge is elusive. The Prophet Jeremiah explains: “More tortuous than anything is the human heart, beyond remedy; who can understand it? I, the Lord, explore the mind and test the heart, Giving to all according to their ways, according to the fruit of their deeds.” (Jer. 17:9-10)

Are you intimidated by these intricacies? Like Bartimaeus, seek the Lord with reckless persistence and beg: “Master, let me receive my sight.” Bartimaeus trusted Jesus to open his eyes. In discovering Jesus, he found himself, his purpose, and his destiny.

What's Your Reaction?